The Funakoshi Okinawan Karate Kenpo Kenkyukai (Research Society & Study Group) is dedicated to studying and researching, in particular, Master Gichin Funakoshi's Okinawan Shorin-ryu karate kenpo teachings. For authoritativeness, Master Gichin Funakoshi's old Okinawan karate, his later developed karate, Master Gigo Funakoshi's karate, the developments of Shoto-kai, & every other karate kenpo lineage, are all considered.

Sunday, 5 December 2021

Bushoru.org Closure

Monday, 8 November 2021

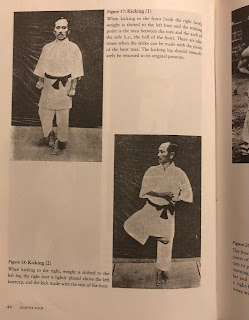

Gichin Funakoshi’s Side-up Kick (Keriage)

Sunday, 31 October 2021

The Name of the Kata Wansū

Thursday, 21 October 2021

Yin and Yang in Karate

It is a myth that karate is a hard martial art in the sense

that it only uses hard techniques. It appears hard, but that is because it is

related to a variety of so-called hard methods, such as Southern Shaolin. The

karate text, Bubishi, does not specify a difference between Northern and

Southern types of gongfu, instead simply noting Shaolin. While the old masters

disagreed over the idea that karate kata were descended either from Shorin-ryu,

using the characters for Shaolin, or Shorei-ryu, using the ideograms for

Zhaoling, supposedly referring to the, or a, Southern Shaolin Temple, the

commonality is that both are a kind of Shaolin boxing. In other words, the sort

of gongfu seen to be harder or external, when compared with Wudang boxing

which, while descended itself from Shaolin, is viewed as being softer or

internal. Although, both Shaolin and Wudang actually teach hard and soft

techniques and methods, as the concept of yin and yang runs deep in Chinese

history and culture.

According to Kanken Toyama (Oyadomari) in

his Introduction to Karate-Do: Its Inner Techniques and Secret Arts (1956 –

translated into English in 2019 by Tobey Stansbury), there are no such styles

as Shorin-ryu and Shorei-ryu in karate, only hard and soft. However, there are

general northern and southern types of Chinese boxing, discussed traditionally

in quanfa through the saying, “Northern legs, southern hands”. Northern-style

gongfu is usually formed in patterns that require a lot of space to perform,

because they are based on the military patterns used for weapons such as

different kinds of swords and the spear. Whereas, southern gongfu is more civilian

based, hence the term “civil fighting arts”. Also, as with other parts of

China, the terrain and weather differ in the south. Therefore, southern boxing

often moves less than northern boxing, and sometimes not much at all. Stances

are not necessarily narrow, but there is more emphasis on solidity while using

the hands and body. Okinawan kenpo, or in other words, karate, is generally

more like the southern kind of Chinese boxing, though there are a range of

influences which have contributed over the centuries to making Ryukyu kenpo

unique to Okinawa. Nonetheless, experts such as Gichin Funakoshi are supported

in their theory on Shorin-ryu (Northern-style Shaolin boxing) and Shorei-ryu

(Southern-style Shaolin boxing; Zhaoling boxing) with, for instance, Wong Kiew

Kit’s 1996 book, The Art of Shaolin Kung Fu, stating on page 38 that “Southern

Shaolin Kung Fu is characterised by solid stances, powerful arms and elaborate

hand techniques, in contrast with the elegant jumping, extensive movements and

wide range of kicking attacks of the Northern Shaolin version.” This is

completely separate from karate, so masters like Gichin Funakoshi were not

wrong in distinguishing between different broad types of boxing; one that is

lighter, and one that is heavier. Master Funakoshi noted that both should be

studied, and this advice fits perfectly with the study of yin and yang as yin

is light while yang is heavy.

In Collins Chinese Dictionary, the character

for yin refers to the negative and the shade, while the symbol for yang refers

to the positive and the Sun, and is masculine. Gichin Funakoshi, in his 1925

text Rentan Goshin Karate Jutsu, translated into English in 2001 by John

Teramoto, described yin and yang in relation to the use of the hands as he had

been taught by his teacher, Anko Asato, as noted in Karate-Do Ichiro

(Karate-Do: My Way of Life), Master Asato always emphasising the differences

between yin and yang. According to the English version, entitled Karate Jutsu, shinite

is the dying hand, female hand, or yang hand, while ikite is the living hand,

male hand, or yin hand. This seems odd or an incorrect translation or typing

error, as yin is female and yang is male. Yet the same sort of description is

given in later books by Gichin Funakoshi, including Karate-Do Kyohan (1935 –

translated in 2005 by Harumi Suzuki-Johnston) and Karate-Do Kyohan (1958 –

translated in 1973 by Tsutomu Ohshima). It cannot, then, be a mistake. I think

it must either mean that both hands can change between types depending on the

situation, or that the living hand is soft and the dying hand is hard.

Regardless, yin is soft and yang is hard, but they rely on each other and are

interrelated and constantly changing, with no beginning or end. This is a

fundamental aspect of Taoism, referring to the beginning of the Universe and

the creation of everything. Indeed, the hand gesture in which you place the

open left palm over the closed right fist is a physical representation of yin

and yang, meaning balance, peace and to stop fighting. That same posture is the

manifestation of the Chinese character for martial (wu in Mandarin, bu is

Japanese and Okinawan). There are quite a number of karate kata that employ

this position, such as jion, jitte, wansu, passai, naihanchi (in a different

manner), and many more.

Gichin Funakoshi stated in Rentan Goshin

Karate Jutsu that karate contrasts to jujutsu in that it can be considered a

“hard” martial art. However, he goes on to write that hard and soft co-exist,

and that grappling techniques can be considered soft which is fundamental to

karate if the student seeks to become truly skilful. Furthermore, Funakoshi

stated in the same text, on page 37 of the English edition, “... the ancient

expression [which] says, ‘Battle exists in the interval between the normal and

the abnormal – without knowing that the abnormal becomes normal, and the normal

changes to the abnormal, how can victory be achieved?’” Immediately following

this, it reads, “Yin and yang have no beginning, action and stillness are not

apparent; unless one knows the Way, who can hope to gain victory?” And then the

end of the paragraph talks about the cardinal principles, which are the same,

albeit later described in a more succinct and refined way, as the three

cardinal points of karate noted by Master Funakoshi in other works, including

in his Twenty Guiding Principles of Karate which were first published in

Karate-Do Taikan in 1938 by Genwa Nakasone, and translated into English in 2003

by John Teramoto. The principles are: Hard and soft application of power,

stretching and contraction of the body, and fast and slow application of

technique, all of which are clearly based on the opposites of yin and yang.

In Karate-Do Tanpenshu (2006), by Patrick

and Yuriko McCarthy, there is an article written by Gichin Funakoshi in 1934

entitled Stillness & Action / Yin & Yang. Funakoshi details the concept

of yin and yang to a degree that shows the reader that he clearly had a great understanding

of this ancient Chinese notion of opposites in the Universe. Indeed it is the

foundation of Chinese martial arts, with some styles such as taijiquan and

taiji mantis going so far as to name their systems after it, taiji referring to

yin and yang after there was nothing in the Universe. The taijiquan classics,

including the Treatise by Master Chang San-feng, written around 1200 AD

according to T’ai Chi Classics by Waysun Liao, 1977 / 1990, the Treatise by

Master Wong Chung-yua, written circa 1600 AD, and the Treatise by Master Wu

Yu-hsiang, who lived from 1812 to 1880, all discuss the principles of yin and

yang when explaining the key points to know regarding the method of Long fist

that is commonly known as taijiquan. Karate could also be called something like

taiji karate (although that could be viewed as being incorrect as it is a

combination of languages). Yet, it already is, in a manner of speaking.

Taikyoku is taiji, but in Japanese. The three taikyoku kata in Funakoshi karate

were developed by either Gigo Funakoshi or his father or both together. In the

1958 Karate-Do Kyohan by Gichin Funakoshi, he wrote about taikyoku being the

first and last kata of a real student of karate. That is because the basics are

fundamental and difficult to master. Yet, taikyoku is taiji and therefore yin

and yang, so the teachings of the natural opposites of life and existence are

supposed to be taught as the foundations and most important lessons in karate.

Morinobu Itoman also discussed yin and yang in Okinawan karate in his 1934

book, The Study of China-hand Techniques, translated by Mario McKenna into

English in 2012. From pages 154 to 156, there is a section called The Way of

Opposites, and the first line reads, “Martial strategy is the way of

opposites.” The third sentence is: “If my opponent employs one strategy, then I

employ its opposite.” In sumo wrestling, I have seen several exponents who were

small and comparably light defeating much larger wrestlers by using the skills

found in soft power, harmonising to use their opponent’s strength against them.

Hence, all complete martial arts study yin and yang; soft and hard; opposites.

In physical practice, the theory of yin and yang applies in many ways from a pure perspective. If there is no weight on one foot, it is completely yin, while the foot bearing your weight is fully yang. The free leg, or yin leg, can be most efficiently employed for kicking or stepping. Meanwhile, the arms and hands are yin on the outside and yang on the inside, yet can be applied in a multitude of manners. For example, checking the opponent’s attack, rather than blocking it in a raw sense, is yin defence. A counter-attack would be yang. All of the various methods of blending with the opponent’s assaults are yin, as they are soft. If, on the other hand, I use a defensive technique in a striking fashion, that is yang. For instance, instead of blending with the attack, I can essentially hit the advancing arm or leg. In addition, rather than just crudely blocking in such a way anywhere, I can select a location, preferring a soft target to a hard one, particularly when using the bones of my own arm. You need stamina and efficiency in fighting, as well as accuracy and speed, but you also need to utilise yin and yang and use your mind to strategise and fight with intelligence. It is better for longevity in a situation and in life to block hard to a soft point such as the upper arm, as opposed to connecting bone with bone more so on the inside and outside of the forearm near the wrist or by the elbow. Iron-body training is great, and you should be confident that you will not be easily hurt, coupled with your ability to evade and your skills in defence. But to rely solely on an iron-like physique is a mistake. As Master Anko Asato taught Gichin Funakoshi, “Think of the hands and feet as swords.” And as Master Funakoshi also wrote in his 20 precepts, “Do not think of winning; think, rather, of not losing.” Hence, focus on defence and do not let your opponent so much as touch you. In addition to this, employing the three cardinal points, as previously noted, as well as moving in accordance, the principles of yin and yang can be applied skilfully and with intellect, enabling, as with the case of certain sumo wrestlers, a small person to defeat someone much larger, no matter how intimidating they may appear.

This essay was written for my 5th Dan exam, which I passed in early January 2022.

Sean Marshall

Sunday, 3 October 2021

So-called Advanced Kata

From sūpārinpē performed in the 1974 footage of Keio karate, which also featured Isao Obata

Suparinpei is taught in Keio University karate, and, according to Sensei Kinichi Mashimo, who learnt directly from Master Gichin Funakoshi and others such as Master Isao Obata (who continued to teach Funakoshi karate at universities such as Keio until he passed away in 1976), Master Gichin Funakoshi supervised the transmission of suparinpei at Keio, resulting in the alterations present in their version, although he did not teach the kata all on his own. It does appear evident that we know which kata he focused on, but that he knew other kata to one extent or another, and was therefore able to make changes to them after they were taught by other teachers to his students. Of course, to be overly concerned with which kata this or that person knew is ridiculous and a waste of time, because, for instance, Goju-ryu does not include gojushiho, and Tomari village tii traditionally taught wansu, wankuan (okan), rohai, naihanchi, passai, perhaps sesan, and maybe one or two other systems, then chinto, ji'in, jitte, chinte (mariti) and plausibly jion, but gojushiho was from Matsumura's tii. It makes no difference if you know suparinpei or gojushiho or any other particular kata that is, nowadays, said to be more advanced. Look at Choki Motobu's example. He only practised one or two kata, focused more on kumite, probably knew many more kata, and was highly skilled, apparently more so than most. My current teacher only teaches five forms: a short version of the actual form, the actual longer form, and three weapons forms. And the short form has 108 movements. Yet, we get by, and most of the time we practise pair-work. As Master Asato said, five or six kata are enough, provided they are studied deeply. And each has its own beneficial characteristics, so they can be selected accordingly, and in harmony with your own body.

Saturday, 2 October 2021

The Karate Kata of Master Gichin Funakoshi

Does this apply to other kata? We know that Master Nakayama, for example, was also sent to learn from others such as Master Mabuni, as he described in an interview. When he returned to Funakoshi with the kata he had been instructed to study, and as they were changed afterwards, to what extent did Funakoshi make those edits?

Saturday, 25 September 2021

Keio Karate Book by Sensei Kinichi Mashimo

Monday, 20 September 2021

Rare Old Keio Funakoshi Karate Footage

Gichin Funakoshi Versus Multiple Opponents

Saturday, 18 September 2021

The Late Master Kazumi Tabata

Friday, 17 September 2021

Footage of Master Isao Obata Performing Kata

Wednesday, 15 September 2021

The Application of Kakidī

Kakidi (kakidī) / kake-te (kakede) is just a form a sticky hands (chi sao), or pushing hands (tui shou) - which is also called striking hands. Kakie is the more well-known version in Okinawa. Gichin Funakoshi noted kake-te in his books. These methods are great for developing sensitivity, better understanding of yin and yang, and grappling, striking, defence and strategy. As Gichin Funakoshi put it, you can learn a lot about your opponent with kakidi. The first version of this type of training which I learnt was a kind of chi sao using both hands. However, while it is beneficial and should be studied, it shouldn’t be focused on as if it is actual fighting itself. Indeed, no single method is fighting other than actual fighting. Every other training method is preparation for real situations. With this, the application of such a method as kakidi or chi sao is to move with your opponent once you’ve actually made contact. An actual fight starts from one distance or another, and sooner or later turns into contact. What do you do at all stages, including when you’ve actually connected? There could be a struggle. What do you do? You can’t think, because you’ll become distracted. You have to feel and harmonise, keeping control of yourself, your opponent, and the situation.

Tuesday, 7 September 2021

Thursday, 8 July 2021

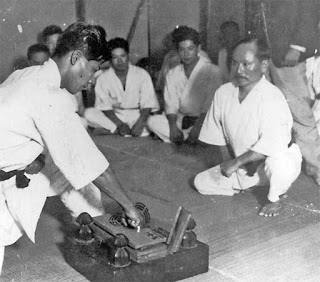

Breaking Boards and Bricks

This is an old practice in China and Okinawa. It is meant to be a way of showing strength of technique and mentality. However, it has been proven many times that it is based on physics and the make-up of whatever is being broken, rather than some special ability to break things that can only be acquired through years of relentless training. By following through in the right way, and by using the right boards, tiles, etc., even a novice can break things. If you want to show something special, rather break something that shouldn’t be breakable. That would be remarkable! Or, better yet, don’t break anything at all because it is wasteful and does not set a good example for our times. I do, however, see the value in the practice for martial development. It can help you to develop confidence in your technique and your hardness, and to improve your ability to follow through your target. But, like I said, it’s an old practice and it is wasteful. If you want to break something, perhaps use stones and then reuse the remains for something in your garden, for example. Or you could create a block of ice and try breaking that. Considering the environment on which depend, reusing, recycling, etc., is a product of the Way. Destroying useful objects is not. Think about it first, and rather devise a method to ensure it is sustainable before callously breaking anything.

Competition in Karate